A Guide to Opposition

How to argue against right-wing positions

Status: December 2024

Sources/helpful links

Facts and arguments on the debate about refugees in Europe and Germany (Pro Asyl)

Pro Asyl: Pro Menschenrechte. Contra Vorurteile.

What to do against hate speech? (Amadeu Antonio Foundation)

Amadeu Antonio Stiftung

Deconstructing slogans and prejudices against gay/lesbian/trans* people

#Respektcheck

Help against hate speech on the internet

Hate Aid

Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen: Helpdesk

Independent reporting centres that remove right-wing extremist, racist and other derogatory content and review it from a legal and youth protection perspective

internet-beschwerdestelle.de

jugendschutz.net

eco Beschwerdestelle

Introduction

In many specialist texts these days, there are reports highlighting the explosive nature of our times. In most cases, they make reference to the polarisation of society and the sudden loss of ability to enter into dialogue with one another. Terms such as “wokeness”, “the old parties” or “foreign infiltration” are pulled like proud turnips from the subterranean depths of the political centre of society. Theories as to how it could have come to this are put forward in talk show formats every evening.

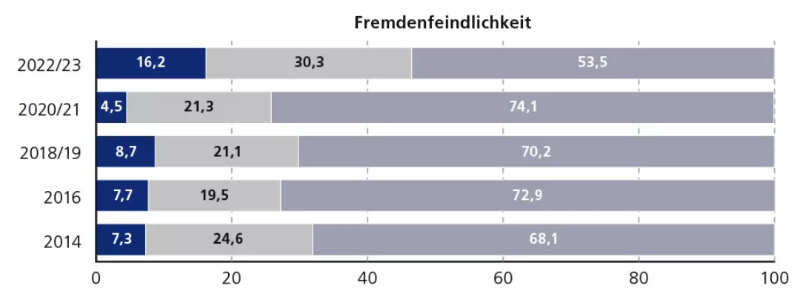

There are two problems with this type of reporting: On the one hand, the abridged presentation harbours the danger of ignoring the creeping development and its historical continuities. There is no zero hour when it comes to right-wing populism, right-wing radicalism and their narratives and continuities. For some time now, democratic pillars have been being successively eroded by right-wing forces. The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung's study of the political centre (”Mitte-Studie”) has been providing information on the spread of right-wing extremist, misanthropic and anti-democratic attitudes in Germany every two years since 2006. The last Mitte-Studie was carried out in 2022/23, with the following results, among others:

“Every twelfth person in Germany shares a right-wing extremist world view. At 8%, the proportion of respondents in the 2022/23 study with a clear far-right orientation has risen considerably compared to the level of just under 2 to 3% in previous years. More than 6% are now in favour of a dictatorship with a single strong party and a leader for Germany (2014–2021: 2–4%). Over 16% assert Germany's national superiority, call for “finally” regaining the courage to have a strong national sentiment and a policy whose primary goal should be to give the country the power and authority it deserves (2014–2021: 9–13%). In addition, almost 6% of respondents now hold social Darwinist views and, for example, agree with the statement “There is life that is valued and life that is not.” (2014–2021: 2–3%). The grey area between rejection and approval of right-wing extremist attitudes has also widened considerably. At 15.5%, the political self-positioning of respondents to the right of centre has also increased significantly from just under 10% previously.” (©Mitte Studie)

This development is more than worrying. It is testimony to the lack of a critical debate on racism in society as a whole. In many places, colleagues, neighbours, family, friends and even people themselves claim to be against discrimination and racism. But being anti-racist requires “the active admission of being part of the problem – even if unconsciously and reflectively. Realising this personal responsibility is a big step in the right direction.” (Guy; Kiromeroglu, Lutz, Yumurtaci: Anti-Rassismus für Lehrkräfte, 2023. p. 12.)

This leads us to the second problem of inflammatory reporting. Instead of pointing out possible strategies for action by highlighting possibilities for intervention against the far-right and referring to civil society stakeholders, such reporting conjures up a threat scenario that we are all at the mercy of.

What luck that we are not! This article aims to show ways in which we can remain capable of acting and learn to use the power of language to exercise the muscle of civil courage on a daily basis. To this end, it is worth first taking a look at discourses and terminology in order to have a common basis for further discussion. The article also provides a brief insight into various patterns of argumentation by right-wing populists and right-wing radicals. The final section covers the numerous opportunities we have to stand up for inclusive and anti-racist spaces in our society.

blue = approval, gray = gray area, lilac = rejection

You can find an English summary of the study here.

What is discrimination?

Germany has many laws that guarantee equal rights, such as the General Equal Treatment Act (AGG). The German constitution also ensures the equality of all people before the law. This means that there is already a solid legal basis for a discrimination-free life. However, despite these laws, unequal treatment of certain groups of people can still be observed in practice, for example in the world of work, in the education system or in access to certain social resources. Discrimination can be subtle, taking the form of prejudices, micro-aggressions or structural inequalities that are more difficult to measure.

We understand discrimination to mean unequal treatment that leads to disadvantage and is linked to the following characteristics, among others:

- Gender and gender identity

- Physical condition

- Sexual identity

- Skin colour

- Religion

- Language and accent

- Age

- Origin

- Political world view

- Appearance and body

The specific forms of discrimination can be classified as categories of group-related misanthropy (Heitmeyer, Wilhelm (Hrsg.): Deutsche Zustände, Folge 1-10, 2002-2011, Suhrkamp Verlag.):

- Racism – anti-Muslim racism, racism against black people, Gadjé racism (i.e. racism against Sinti and Roma people), anti-Asian racism, anti-Slavic racism, etc.

- Anti-Semitism – hostility towards people of the Jewish religion

- Adultism – discrimination against young people

- Ableism – discrimination against people who are and become disabled

- Classism – discrimination against people based on their social background

- Sexism – discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation

- Etc.

Intersectionality is an important insight when dealing with specific forms of discrimination. It describes the phenomenon of different kinds of discrimination mutually influencing and reinforcing each other rather than simply adding up. Intersectionality is like a lens that allows us to see where power comes from, who or what it encounters and where there are links or blockages. It’s not simply that there is a racism problem here and a gender problem there, a class problem here and an LGBTQIA+ (stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual and other people affected by hetero-sexism) problem elsewhere. The focus on a single form of discrimination often obscures what is actually happening: namely the interplay of several ideologies of inequality at the same time (according to Kimberlé Crenshaw).

Even if laws guarantee equal rights, there are often deeply rooted social norms, prejudices and stereotypes that favour discrimination. These are difficult to measure and even more difficult to resolve. Lengthy educational and awareness-raising processes are required, as well as a change in social attitudes. And even if change often takes several generations to overcome deep-rooted inequalities and discrimination, it is always worth fighting for. Individually and institutionally, it is important to take responsibility and stand up to all forms of marginalisation and unequal treatment. It's not always easy, because how can you intervene and discuss when there is a fine line between expressing a different opinion and inflammatory hate speech?

Right-wing extremism vs. right-wing populism

Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism are two political phenomena that are often confused with each other, but differ in several important aspects. Both belong to the right-wing political spectrum. But it gets tricky when we look at the ideologies, their attitudes to democracy and the means they use.

Right-wing extremism

Right-wing extremism is an umbrella term for political attitudes that reject democracy and the equality of all people. One’s own nation is considered to be superior and of higher value. Racism, nationalism, anti-Semitism, nationalistic thinking and a rejection of pluralism are central components of right-wing extremism. Organised right-wing extremist groups, as well as individuals, tend to regard violence as a legitimate means of achieving their political goals. This is often directed against people and groups that do not fit into their world view. Other typical characteristics of right-wing extremists are the trivialisation of National Socialism, historical revisionism and a penchant for conspiracy narratives.

The organised far right consists of many different groups and movements that differ in their ideological orientation: far-right parties, associations, vigilante groups, comradeships, so-called “citizens of the empire”. The following groups are currently involved: the NPD (far-right party), Der III Weg (nationalist movement), AfD and JA (far-right party), Identitäre Bewegung (radical right-wing youth movement), HoGeSa (extreme right-wing group).

Right-wing populism

Right-wing populists represent populist ideas that are based on criticising the political elite, anti-establishment rhetoric and the idea that they represent the true interests of the people. They present themselves as the (only) voice of the “people” (at the bottom), setting themselves apart from the “corrupt elites” (at the top). Their political strategy is to polarise and emotionalise debates. To achieve this, they rely on racist prejudices and a “perceived” insecurity of the population. When enough horror scenarios have been painted, right-wing populists are quick to suggest a need for action and offer supposedly simple, radical “solutions” to complex crises and political and economic conflicts. They often blame migrantised and/or racialised groups of people for social ills.

Right-wing populist strategies contribute to making right-wing extremist ideas utterable and socially acceptable again, which lowers the inhibition threshold for physical violence. What both phenomena have in common is that they pursue an anti-queer, sexist, racist, ableist and democracy-weakening agenda.

Patterns of argumentation used by the right

In order to confront right-wing populist and other anti-democratic statements, it is necessary to engage with the typical patterns of argumentation used by the right and their forms. A whole range of rhetorical manoeuvres can be used to steer conversations. If we are able to recognise these in a conversation with a right-wing populist, then we are prepared for the traps. In this way, we can confront them in an argumentative and objective manner. Some of these typologies are listed below:

- “Topic hopping”

In order to create confusion and avoid having to give reasons, the content hops from one topic to another. - “Ironisation”

Here, people and issues are ridiculed with aggressively mocking terms. - “Stooge”

Here, a supposed opposing position is misrepresented or distorted and presented as unrealistic, thereby strengthening one's own position and demands.

- “Majority appropriation”

Own demands are justified by the alleged will of a majority in order to give them more weight. - “Whataboutism”

Attention is diverted from one topic to another context (“But what about...?”). This is an attempt to relativise the actual topic and prevent a discussion. - “Dog-whistling”

This is the use of terms whose meaning is understood by those who think alike, but which can be dismissed as a misunderstanding if criticised. Derived in this sense from the fact that humans are unable to hear the sound made by dog whistles. - “Generalisation”

Individual cases are used to draw conclusions about a group as a whole in order to seemingly confirm racist and discriminatory prejudices. - “Victim staging”

Central to this is the portrayal of oneself as a misunderstood victim of an alleged dictatorship of opinion. This avoids criticism of anti-human or anti-democratic statements. - “Pseudo context”

A thematic connection is constructed where there is none. This allows two groups to be played off against each other and simple solutions to be offered for complex problems (Sag Was. Mischen und Einmischen gegen Rechtspopulismus, 2021).

Interventions – The power of contradiction

We’ve all experienced them – the sudden turns in conversations when everything had seemed relaxed a short time before: at work, at a party, at a family gathering or in the digital space. It is the moment when the person we are talking to suddenly starts repeating slogans that reflect hatred and misanthropy instead of their own opinion. In our immediate surroundings and beyond, be it at the bus stop, in a public building or in a café, we are naturally confronted with perspectives that do not always correspond to our opinion. But the question we should ask ourselves is: Is what we have heard an opinion that stems from a political conviction?

Opinion is a protected right in a democracy as long as it remains within the law and does not injure others. In Germany, for example, Article 5 of the Constitution protects freedom of speech. However, hatred is not covered by freedom of speech if it violates the rights of others or jeopardises public order. Hate speech or hate crime (such as racist or anti-Semitic hate speech) is prohibited by law. Opinions, even if they are critical or controversial, can be expressed and discussed in a respectful environment without causing harm. Hate and hate speech, however, have concrete harmful effects on the social climate. They lead to division, polarisation and violence.

Listed below are some key questions that can help you recognise the type of speech situation and strengthen your own options for action.

How safe do I feel?

The basis of any intervention should be to assess the risk situation for yourself in advance. For example, if I am a person who is affected by racism and/or queer hostility, then the danger to my physical and mental integrity is far greater than for a white heterosexual person. So what would make me feel safe and remain capable of acting? Who can support me? And in general: How am I feeling today? How much strength and energy do I have for a conflict?

Who do I hope to reach through an intervention?

Emotionalised conversational situations are often confusing. If racist or conspiracy-theory statements have been made, I may not even be able to reach the person who made the discriminatory comments. Who else could I reach? Persons potentially injured by the statement? Here it is important to consider invisibility and to always assume that there may be people affected by discrimination in every room. Or silent followers who agree with the statement but do not appear themselves and therefore have reflective potential? Silent allies who do not (yet) dare to react themselves? Loud allies who could use some support?

What are the general conditions?

Discussions are frustrating if, in addition to the heated debate, the general conditions are inappropriate. It is therefore helpful to check how much time and space I have. Do I run the risk that my reaction will not be sustainable because, for example, the event ends in five minutes or the train arrives in two minutes? How can I adjust the conditions accordingly? And do I even want that?

Who is speaking?

The text above explains various characteristics of right-wing extremist and right-wing populist groups. If I find myself in an argument because of a racist statement, I should ask myself who made the discriminatory comment. Many right-wing extremists have a closed world view based on fixed, often dogmatic convictions that leave little to no room for critical debate or counter-ideas. People who are trapped in a closed world view often find it difficult to question their own view. Self-criticism and reflection are often undesirable in right-wing extremism, as they would destabilise the entire ideological construct. For a discussion, however, it is essential to at least have the willingness to change one's own opinion or to learn about and respect new points of view.

Welche Rahmenbedingungen gibt es?

Diskussionen sind frustrierend, wenn zusätzlich zur hitzigen Debatte die Rahmenbedingungen unpassend sind. Daher ist es förderlich abzuchecken, wie viel Zeit und Raum ich habe. Laufe ich Gefahr, dass meine Reaktion wenig nachhaltig ist, da zum Beispiel die Veranstaltung in fünf Minuten endet oder die Bahn in zwei Minuten kommt? Wie kann ich die Konditionen entsprechend anpassen? Und möchte ich das überhaupt?

Wer spricht?

Im Text weiter oben werden verschiedene Charakteristika von rechtsextremen und rechtspopulistischen Gruppierungen erläutert. Befinde ich mich in einer Auseinandersetzung aufgrund einer rassistischen Aussage, sollte ich mich fragen, von wem die diskriminierende Äußerung kommt. Viele Rechtsextremist*innen haben ein geschlossenes Weltbild, das auf festen, oft dogmatischen Überzeugungen beruht, die wenig bis gar keinen Raum für kritische Auseinandersetzung oder Gegenvorstellungen lassen. Menschen, die in einem geschlossenen Weltbild gefangen sind, haben oft Schwierigkeiten, ihre eigene Sichtweise zu hinterfragen. Selbstkritik und Reflexion sind im Rechtsextremismus häufig nicht erwünscht, da sie das gesamte ideologische Konstrukt destabilisieren würden. Für eine Diskussion ist es jedoch unerlässlich, zumindest die Bereitschaft zu haben, die eigene Meinung zu ändern oder neue Sichtweisen kennenzulernen und zu respektieren.

Argumentation techniques and strategies

Sometimes we would like to intervene and remain capable of acting, to rebel against right-wing agitation and to stand up to our right-wing populist counterparts. But then we lose our courage because we are convinced that we lack the relevant information and specific knowledge to refute right-wing arguments. That doesn't matter. We shouldn’t be afraid of not knowing enough about topics. We don't want to argue anyone up against the wall. We just don’t want to simply leave inflammatory, racist, sexist and derogatory statements unchecked, as this could be interpreted as approval. So even with little knowledge we can still do the following:

- Point out generalisations (Islam, the image of women, etc.)

E.g. “What exactly do you mean by “Islam”?” There are almost two billion Muslims worldwide – how realistic is it that there is only one form?” - Point out group assignments (“we” vs. “they”)

E.g. “Who do you mean by “we” and “they”?” or “Could it be that in the idea of an “us/we” there are also people who are more diverse?” Such as family, friends, acquaintances. - Point out inconsistencies in the argumentation and ask questions

E.g. “What do you mean exactly?” or “On the one hand you explain...., but on the other hand you say.... – I don't understand that, can you explain it without contradictions?” - Demand solutions and point out consequences

E.g. “What would be your specific solutions to the problems mentioned?” or “If that were the solution, what do you think would happen to the weaker members of society, who already have fewer resources at their disposal?” - Express discomfort

E.g. “I find your statement questionable/not okay/hostile/etc.” - Enquire about the background to the statement

E.g. “Can you tell me where your assumption comes from?” or “How did you come up with this idea?” - Ask questions of comprehension

E.g. “What exactly do you mean?” or “What do you mean by that?” - Ask for clarification

E.g. “Can you please explain XY again? That will help me understand it better.” - Ask for specifics

E.g. “If you mean that EVERYONE does something or that something ALWAYS happens, can you please give me some specific examples?” - Request sources

E.g. “On what sources is your theory based?” - Ask for the speaker’s perspective

E.g. “From which perspective are you speaking?” or “Would you say you are affected by XY yourself?”

Using humour as a strategy gives us the distance we sometimes need to keep a cool head in difficult debates. This should be distinguished from the aggressive humour of right-wing extremists who make discriminatory jokes and mock marginalised groups of people. So, our response to a right-wing statement could be to:

- Express a (supposed) appreciation, for example: “It's great that you bring up the subject. We're planning to look into this at some point anyway.”

- React with irony

- Lead the person up the garden path

If the person you are speaking to, who is expressing right-wing opinions, does not accept minimum democratic standards such as human rights and minority rights, it is necessary to clearly differentiate oneself and demonstrate a clear position:

- Set a boundary that shows that what is being said contradicts your own values

- Show indignation

- Make clear that you are personally affected

- Make the consequences clear, e.g. refer to house rules, the law, the criminal relevance of the statement, etc

- Adopt an opposing position

Right-wing populists are often skilled speakers who know numerous rhetorical tricks that allow them to dominate the conversation. The argumentation patterns described above can tempt us to put our own thread and our arguments to the back of the queue. We would therefore like to remind you here to strengthen your own position and perspective and to take a critical look at the statement of your counterpart (transparently for all):

- When confronting right-wing populists, don't limit yourself to opposing what they say – instead, go on the offensive with your own topics and content!

- Use strong counter-terms

- Set diversity and participation against each other as a cross-cutting issue Ask for examples named and provide counterexamples

- Draw comparisons

- Involve the other people in the room

- Demand a change of perspective

- Ask the person to take a look in the mirror

- Ask “What if...?” questions”